Published: 6th October 2023

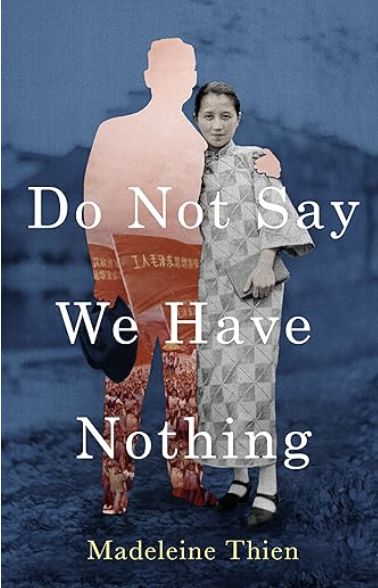

Do Not Say We Have Nothing Synopsis:

Madeleine Thien’s Do Not Say We Have Nothing is a complex and moving historical fiction that largely takes place in revolutionary China, spanning from the first days of Chairman Mao’s ascent, to the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989.

In 1990, ten-year-old Marie and her mother invite Ai-Ming, who fled China in the aftermath of the Tiananmen Square protests, into their home in Canada.

The relationship between Ai-Ming and Marie deepens and Ai-Ming tells the story of her family in China, presenting a history of revolutionary idealism, music, and silence. The story centers around three musicians: The composer Sparrow, the violin prodigy Zhuli, and the pianist Jiang Kai. Through evocative storytelling, Madeleine Thien presents their struggle during the Cultural Revolution to stay loyal to one another and to their music. Their fates have a lasting impact through the years, and deep consequences for Marie and Ai-Ming.

My Thoughts:

Having studied revolutionary China in history at higher level at school, this book was very immersive for me. I kept reading about events that came up when I learnt about Communist China, like the Hundred Flowers Campaign, the Great Leap Forward, and the Cultural Revolution, and this made the experience of reading this book very enjoyable. I’m also very passionate about music, which is an integral part of this book, being a large part of the identities of many characters in this book, and this also added to my love of this novel.

I have read in some reviews the argument that this book is overly complex. I do feel that this book could be a lot more difficult to read for someone who doesn’t know anything about music and hasn’t learnt about the history of China. However, I think this book is actually great for these people, because it teaches so much about the history of China but in a way that is poignant and riveting. I feel if I read this book knowing nothing about China beforehand, it would have taught me so much, and made me want to learn more, even if it took me longer to read.

As I read this book I kept thinking to myself that if I had read this during school I would have remembered so much more for my exam, as Thien’s way of storytelling made the events throughout the book very memorable. I admired the way she was able to weave music, the characters, and the actual historical events together into one powerful story.

Thien strongly presented the effect of oppression on individual identity. The Cultural Revolution makes the music in the lives of the three musicians a reason for persecution, but it does not escape their minds as it is still a big part of their identity throughout the novel. (This reminded me, in a way, of Andreï Makine’s A Life’s Music, which also had music as an integral part of the central character’s identity). She shows how the Communist party wants the musicians to play only revolutionary music, but how they continue to play the music that they love, for creative expression. This has strong consequences for the characters.

She captures the various horrific effects of political oppression. She shows the isolation and the division of communities, that it causes, through the isolation of Marie and her mother as a result of Kai’s suicide (a result of political oppression), and through the individual actions of family members who turn on each other in order to survive. She also shows the traumatic effects that it has on the convicted “rightists”, who are sent to brutal concentration camps or killed.

Madeleine Thien shows through this novel the power of storytelling to record the lives of those who suffer in history and thus deliver powerful messages about the world. The “Book of Records” plays an important part throughout this novel, and it becomes clear that this book is in itself a Book of Records, with some stories left untold, just as is the case in the fictional one. The story is never truly over, but as we go through life, we try to see a little more.

Quotes:

“All of my unanswerable questions seemed to circle within the notes, at the intersection of piano and violin, between the music and the pauses, the rests. How did a composer live his life unheard? Could music record a time that otherwise left no trace?”

“What mattered most in this moment: the words on the posters of the lives – of her parents, of Ba Lute and Sparrow – in suspension, the promise of Mao Zedong thought or the day-to-day reality of New China? Which would win out, the Shanghai of utopia, or the city of the real?”

“I assumed that when the story finished, life would continue and I would go back to being myself. But it wasn’t true. The stories got longer and longer, and I got smaller and smaller. When I told Big Mother this, she laughed her head off. ‘But that’s how the world is, isn’t it?’”

“But he had never known how to write music, to perform music, and yet be silent.”

“In the end, I believe these pages and the Book of Records return to the persistence of this desire: to know the times in which we are alive. To keep the record that must be kept and also, finally, to let it go. That’s what I would tell my father. To have faith that, one day, someone else will keep the record.”

“Arise, slaves, arise!

Do not say that we have nothing.

We shall be the masters of the world!”

“Yes, things could still change, not for her, not for Sparrow, but for Ai-Ming. She could not stop her own heart from breaking. But for her daughter behind this mountain was another mountain, behind this sea, another sea.”

“She told me, Wen the Dreamer, it’s foolhardy to think that a story ends. There are as many possible endings as beginnings.”

“It’s just as Wen the Dreamer said: she could take the names of the dead and hide them, one by one, in the Book of Records, alongside May Fourth and Da-Wei. She would populate this fictional world with true names and true deeds. They would live on, as dangerous as revolutionaries but as intangible as ghosts.”